#include <stdio.h>

int add(int a, int b)

{

int c = a+b;

printf("@add(): &a=%p, &b=%p\n", &a, &b);

return c;

}

int main()

{

int i = 3;

int j = 4;

int k = add(i,j);

printf("@main(): &i=%p, &j=%p, &k=%p\n", &i, &j, &k);

return k;

}

I made a test in Dev-C++ (version 5.7.1, with MinGW GCC 4.8.1 32-bit), and in debug mode, via the CPU Window it produced the following instructions:

procedure main:

0x004016e0 <+0>: push %ebp 0x004016e1 <+1>: mov %esp,%ebp 0x004016e3 <+3>: and $0xfffffff0,%esp 0x004016e6 <+6>: sub $0x20,%esp 0x004016e9 <+9>: call 0x401cc0 <__main> => 0x004016ee <+14>: movl $0x3,0x1c(%esp) 0x004016f6 <+22>: movl $0x4,0x18(%esp) 0x004016fe <+30>: mov 0x18(%esp),%edx 0x00401702 <+34>: mov 0x1c(%esp),%eax 0x00401706 <+38>: mov %edx,0x4(%esp) 0x0040170a <+42>: mov %eax,(%esp) 0x0040170d <+45>: call 0x4016b0 <add> 0x00401712 <+50>: mov %eax,0x14(%esp) 0x00401716 <+54>: lea 0x14(%esp),%eax 0x0040171a <+58>: mov %eax,0xc(%esp) 0x0040171e <+62>: lea 0x18(%esp),%eax 0x00401722 <+66>: mov %eax,0x8(%esp) 0x00401726 <+70>: lea 0x1c(%esp),%eax 0x0040172a <+74>: mov %eax,0x4(%esp) 0x0040172e <+78>: movl $0x40507a,(%esp) 0x00401735 <+85>: call 0x4036c8 <printf> 0x0040173a <+90>: mov 0x14(%esp),%eax 0x0040173e <+94>: leave 0x0040173f <+95>: ret

subroutine add:

0x004016b0 <+0>: push %ebp 0x004016b1 <+1>: mov %esp,%ebp 0x004016b3 <+3>: sub $0x28,%esp 0x004016b6 <+6>: mov 0x8(%ebp),%edx 0x004016b9 <+9>: mov 0xc(%ebp),%eax 0x004016bc <+12>: add %edx,%eax 0x004016be <+14>: mov %eax,-0xc(%ebp) 0x004016c1 <+17>: lea 0xc(%ebp),%eax 0x004016c4 <+20>: mov %eax,0x8(%esp) 0x004016c8 <+24>: lea 0x8(%ebp),%eax 0x004016cb <+27>: mov %eax,0x4(%esp) 0x004016cf <+31>: movl $0x405064,(%esp) 0x004016d6 <+38>: call 0x4036c8 <printf> 0x004016db <+43>: mov -0xc(%ebp),%eax 0x004016de <+46>: leave 0x004016df <+47>: ret

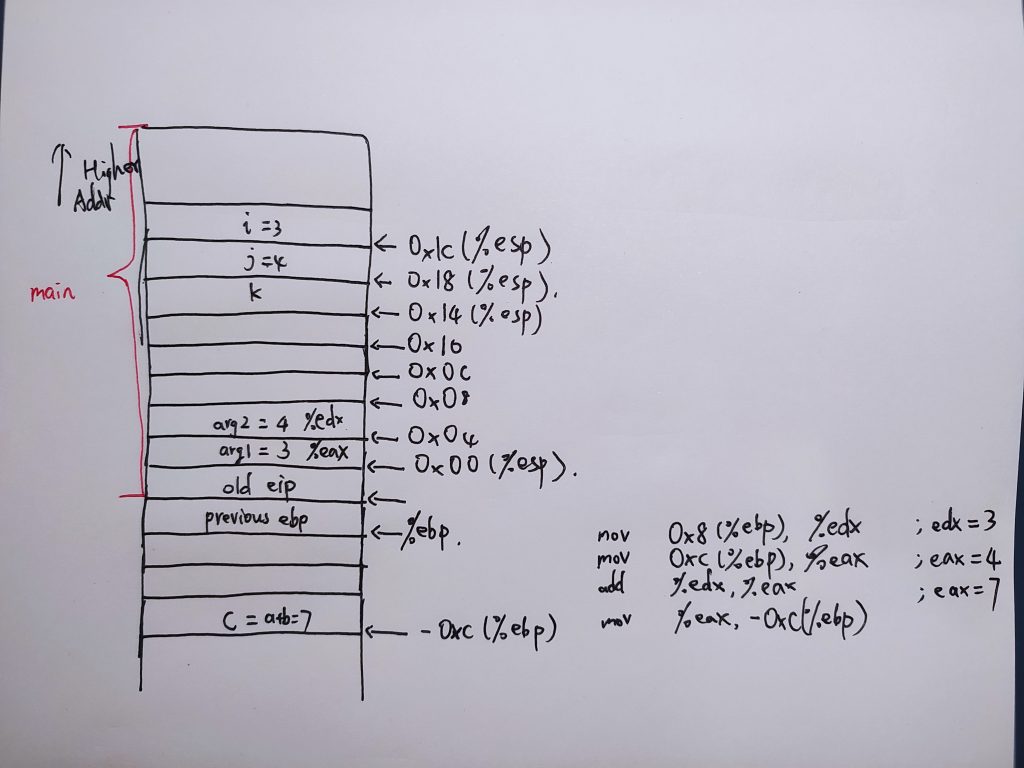

Following these instructions, I drew a simple diagram (partial, incomplete):

The arguments for printf were left out in this diagram for simplicity, but it is not difficult to imagine the whole running process with the aid of the above instructions. The calling convention, however, can be different from another compiler. For example, on my Ubuntu 20.04.1 LTS server with GCC 9.3.0, it yields something like

@add(): &a=0x7ffdf0f69a3c, &b=0x7ffdf0f69a38 @main(): &i=0x7ffdf0f69a6c, &j=0x7ffdf0f69a70, &k=0x7ffdf0f69a74

which is completely the opposite of the above diagram: the passed arguments were arranged in decreasing addresses, and the local vars were placed in increasing addresses. For local variables, the compiler knows in advance how much space should be allocated in the stack by looking at its symbol table. Then it allocates enough space by subtracting some value from the RSP register. Thus, it looks like the compiler can place the local vars wherever it likes, it just needs to perform some arithmetics based on the RSP or RBP register. A good explanation for the locations of the passed arguments is, as opposed to storing them on the caller stack, it first copies those arguments to registers (if possible) in reverse order and then saves them to the callee stack near the beginning in argument order (RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, R9). In this way, the value in the EDI register (1st argument) is first placed into the callee stack and hence it has a higher address. Aha! Now it makes perfect sense! Next, let’s check it out by looking at the disassembly by running gdb a.out -batch -ex 'disassemble/s main' (or add).

Dump of assembler code for function main:

add.c:

11 {

0x00000000000011a7 <+0>: endbr64

0x00000000000011ab <+4>: push %rbp

0x00000000000011ac <+5>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x00000000000011af <+8>: sub $0x20,%rsp

0x00000000000011b3 <+12>: mov %fs:0x28,%rax

0x00000000000011bc <+21>: mov %rax,-0x8(%rbp)

0x00000000000011c0 <+25>: xor %eax,%eax

12 int i = 3;

0x00000000000011c2 <+27>: movl $0x3,-0x14(%rbp)

13 int j = 4;

0x00000000000011c9 <+34>: movl $0x4,-0x10(%rbp)

14 int k = add(i,j);

0x00000000000011d0 <+41>: mov -0x10(%rbp),%edx

0x00000000000011d3 <+44>: mov -0x14(%rbp),%eax

0x00000000000011d6 <+47>: mov %edx,%esi

0x00000000000011d8 <+49>: mov %eax,%edi

0x00000000000011da <+51>: callq 0x1169 <add>

0x00000000000011df <+56>: mov %eax,-0xc(%rbp)

15 printf("@main(): &i=%p, &j=%p, &k=%p\n", &i, &j, &k);

0x00000000000011e2 <+59>: lea -0xc(%rbp),%rcx

0x00000000000011e6 <+63>: lea -0x10(%rbp),%rdx

0x00000000000011ea <+67>: lea -0x14(%rbp),%rax

0x00000000000011ee <+71>: mov %rax,%rsi

0x00000000000011f1 <+74>: lea 0xe22(%rip),%rdi # 0x201a

0x00000000000011f8 <+81>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x00000000000011fd <+86>: callq 0x1070 <printf@plt>

16 return k;

0x0000000000001202 <+91>: mov -0xc(%rbp),%eax

17 }

0x0000000000001205 <+94>: mov -0x8(%rbp),%rsi

0x0000000000001209 <+98>: xor %fs:0x28,%rsi

0x0000000000001212 <+107>: je 0x1219 <main+114>

0x0000000000001214 <+109>: callq 0x1060 <__stack_chk_fail@plt>

0x0000000000001219 <+114>: leaveq

0x000000000000121a <+115>: retq

End of assembler dump.

Dump of assembler code for function add:

add.c:

4 {

0x0000000000001169 <+0>: endbr64

0x000000000000116d <+4>: push %rbp

0x000000000000116e <+5>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x0000000000001171 <+8>: sub $0x20,%rsp

0x0000000000001175 <+12>: mov %edi,-0x14(%rbp)

0x0000000000001178 <+15>: mov %esi,-0x18(%rbp)

5 int c = a+b;

0x000000000000117b <+18>: mov -0x14(%rbp),%edx

0x000000000000117e <+21>: mov -0x18(%rbp),%eax

0x0000000000001181 <+24>: add %edx,%eax

0x0000000000001183 <+26>: mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

6 printf("@add(): &a=%p, &b=%p\n", &a, &b);

0x0000000000001186 <+29>: lea -0x18(%rbp),%rdx

0x000000000000118a <+33>: lea -0x14(%rbp),%rax

0x000000000000118e <+37>: mov %rax,%rsi

0x0000000000001191 <+40>: lea 0xe6c(%rip),%rdi # 0x2004

0x0000000000001198 <+47>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x000000000000119d <+52>: callq 0x1070 <printf@plt>

7 return c;

0x00000000000011a2 <+57>: mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

8 }

0x00000000000011a5 <+60>: leaveq

0x00000000000011a6 <+61>: retq

End of assembler dump.

The above assembler code agrees with our speculation. Note, however, the location of the local variable c here. It is above the two arguments in the stack (just one position below the RBP register). If we rewrite the main function as int main(int argc, char** argv), then we can get something like

0x00000000000011a7 <+0>: endbr64 0x00000000000011ab <+4>: push %rbp 0x00000000000011ac <+5>: mov %rsp,%rbp 0x00000000000011af <+8>: sub $0x30,%rsp 0x00000000000011b3 <+12>: mov %edi,-0x24(%rbp) 0x00000000000011b6 <+15>: mov %rsi,-0x30(%rbp) 0x00000000000011ba <+19>: mov %fs:0x28,%rax 0x00000000000011c3 <+28>: mov %rax,-0x8(%rbp) 0x00000000000011c7 <+32>: xor %eax,%eax

in the setup of the stack of main. We can see that the two passed arguments argc and argv are stored at the stack top via the EDI and RSI registers, respectively.

(Jul 15, 2023)

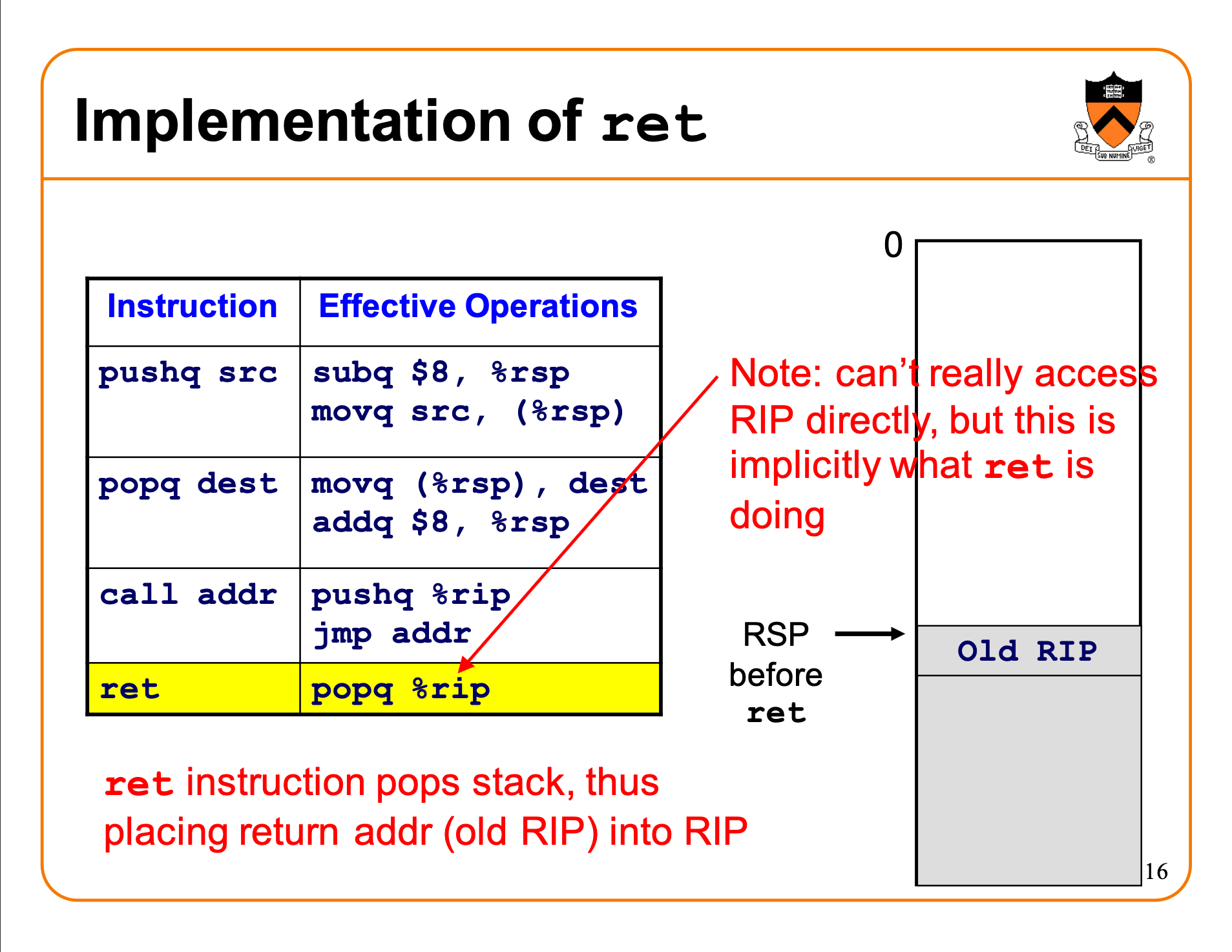

Effective implementations of some x86 instructions (slides from here):